Ah, the harvest season! It’s finally time to enjoy the literal fruits of our labor in the Teaching Gardens and in our gardens at home, right?

Al-most!

There’s a critical step between watching those glittering fruits and dew-speckled veggies mature in the garden and being able to devour them: successful harvesting. Harvesting seems like a simple process – and don’t get us wrong, it is – but it’s also a step that, if done improperly, can wind up spoiling your produce or impeding future harvests. Correct harvesting isn’t always as simple as yanking the veg off the vine and it can be the difference between one delicious bell pepper and that full peck of peppers you were anticipating. In short, it’s worth committing a few tips to memory.

There are three important considerations when harvesting: when to harvest, how to harvest and how to store your veggies if you’re not planning to start the devouring straight away. Below, we go through some common crops and outline how to take them from your garden to your table with maximum flavor and nutrition. Take these tips to your garden and, with a little practice, you’ll be a harvesting pro!

Tomatoes: Tomatoes come in all shapes, sizes and colors, ranging from classic red to pink to yellow, purple and even white. Tomatoes are fully ripe when the fruit is firm, but not hard, and the tomato is uniform in color, which makes it especially important to be familiar with the variety you’re growing. For example, you’ll miss out entirely on your Sun Gold cherry tomatoes if you’re waiting for them to turn red because this variety turns a deep, brilliant orange when ripe. Ripe tomatoes should twist off easily from the vine.

Ripening tomatoes are prone to splitting, which occurs, usually after heavy rain, when the fruit inside grows faster than the peel on the outside and causes the skin to burst. Keep an eye on the forecast: if you’re due for a particularly rainy week and your tomatoes are close to ripe, pick any that are ripe or near-ripe to avoid this.

If you’ve picked your tomatoes before they are fully ripe, or even when they’re green, they’ll continue to ripen indoors on a windowsill. Once they reach peak ripeness at room temperature, by all means eat them! If you can’t eat them immediately, a short stint in the refrigerator won’t hurt; just give them about half a day back on the shelf to recover some of their flavor and aroma afterwards.

Squash/Zucchini: Squash and zucchini are harvested when they reach about 6-8 inches in length. Have you ever thought you caught them all, and then, days later, discovered a torpedo-sized fruit among the foliage? While your monster squash might win you a contest somewhere, baseball bat fruits aren’t ideal for eating. The skin will be tough and the inside will be mostly wet, seedy membrane instead of creamy, melt-in-your-mouth squash. Be diligent about checking your plants at least every other day while they’re are producing. This regular harvesting will spur plant production and ensure your harvest doesn’t get ahead of you. To harvest, cut the fruit off the vine using a sharp blade (pruners, a sharp knife, scissors), and leave about 1 inch of stem on the fruit. Refrigerate, unwashed, in the crisper drawer for up to one week.

Squash/Zucchini: Squash and zucchini are harvested when they reach about 6-8 inches in length. Have you ever thought you caught them all, and then, days later, discovered a torpedo-sized fruit among the foliage? While your monster squash might win you a contest somewhere, baseball bat fruits aren’t ideal for eating. The skin will be tough and the inside will be mostly wet, seedy membrane instead of creamy, melt-in-your-mouth squash. Be diligent about checking your plants at least every other day while they’re are producing. This regular harvesting will spur plant production and ensure your harvest doesn’t get ahead of you. To harvest, cut the fruit off the vine using a sharp blade (pruners, a sharp knife, scissors), and leave about 1 inch of stem on the fruit. Refrigerate, unwashed, in the crisper drawer for up to one week.

Peppers: Bell peppers are harvested when firm, glossy, and fully grown, usually at about 3-4 inches in size. To harvest the fruit, use a sharp blade, leaving about an inch of stem on the pepper; yanking or trying to twist off the fruit risks uprooting the whole plant and bringing about a sudden, tragic end to your pepper harvest season. Avoid this.

Green peppers are technically unripe bell peppers. Given sufficient time, your bell peppers will turn red, orange, yellow, purple or brown depending on the variety you’ve chosen, and as their color develops, the flavor will get sweeter.

For hot peppers, the longer they are kept on the vine, the more the heat will intensify. Refrigerate whole, unwashed peppers for 1-2 weeks in the crisper drawer.

Broccoli: What we know as broccoli is truly a collection of teeny flower buds clustered together to form a head at the center of the broccoli plant. The best time to harvest the broccoli head is when it’s 4-8 inches across (depending on variety), is dark green, and the flower buds are still tight. Any sign of swelling or hint of yellow indicates that the buds are about to flower and the head is past its peak. Cut the mature head off with a sharp knife, leaving about 2-3 inches of a single, thick stem. After this first harvest, side sprouts will spring from the leaf joints of the plant and can be harvested in abundance for weeks to come. Store unwashed broccoli in an airtight container in the refrigerator. Cooked broccoli freezes well.

Swiss Chard and Kale: Chard and kale are prolific vegetables. Individual plants will produce from early spring into late fall, and continual harvesting will spur the plant to keep growing. To harvest, remove the leaves at the bottom of the stalk with a knife or clippers. The inner leaves will continue to mature and will be ready for your next harvest. Store unwashed leaves, wrapped in a damp towel or in a container in the refrigerator for up to 1 week.

Greens: Harvest lettuce leaves when they’re young and tender; if your plants are under heat stress, this can help to stave off bolting. It’s also best to pick early in the day when the leaves are least bitter. If you have lots of plants, harvest the outside leaves from several plants by using a sharp knife, carefully cutting each leaf off at the base. If you want to remove an entire head of lettuce, again, use a sharp knife and cut the head off at just above ground level. Tender salad greens are best used within a few days. Wrap unwashed greens in a damp towel and place them in a plastic bag in the refrigerator. If your greens wilt between the garden and the kitchen, they can be reinvigorated somewhat by submerging them in ice water for about 15 minutes.

Arugula, like lettuce, is best harvested when young. If you wait too long, the arugula will become tough and incredibly spicy. Using a sharp knife, cut leaves off your plants when they reach 2-3 inches in length. Store like lettuce in the refrigerator.

Beets: With all root crops, the trick is knowing when they’re ready. The easiest way to do this is to dig down and feel around the base of the stems of the beet to determine the root size with your finger. Beets are ready to be harvested when they reach about 1½-2” in diameter. Gently pull the plant up from the soil, careful not to disturb other nearby beets that are not yet ready for harvest. Beet greens are delicious, particularly when juiced. Cutting about an inch away from the root, remove the greens and store as you would lettuce or arugula. Keep the roots unwashed and in an airtight container in the crisper drawer where they’ll store for several weeks.

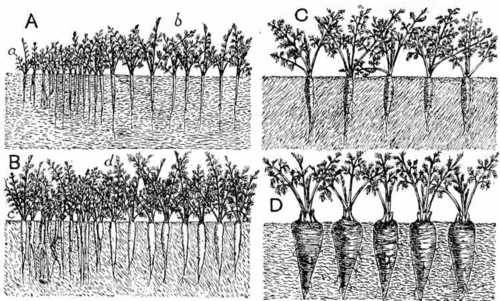

Carrots: Similar to beets, you can determine the size of a carrot by feeling around the base of the greens with your finger. They may be pulled up when the roots are ½ – 1” in diameter. Pull the carrots gently and straight up from the earth. As with beet greens, carrot greens make a great addition to juices. Cut or twist off the tops and placed the roots unwashed in the crisper drawer for up to 4 weeks.

Onions: Onions are ready to be harvested when their tops fall over naturally and the leaves shrivel and turn brown. After you dig up the bulbs, you may set them aside in a sunny, airy location for 3 to 7 days to dry, or cure. Do not refrigerate onions. After drying, store in a cool, dry place, (ideally 40-50F) and they will keep for months. Store cut onion in the refrigerator in an airtight container and use as soon as possible.

Happy harvesting!

Squash/Zucchini: Squash and zucchini are harvested when they reach about 6-8 inches in length. Have you ever thought you caught them all, and then, days later, discovered a torpedo-sized fruit among the foliage? While your monster squash might win you a contest somewhere, baseball bat fruits aren’t ideal for eating. The skin will be tough and the inside will be mostly wet, seedy membrane instead of creamy, melt-in-your-mouth squash. Be diligent about checking your plants at least every other day while they’re are producing. This regular harvesting will spur plant production and ensure your harvest doesn’t get ahead of you. To harvest, cut the fruit off the vine using a sharp blade (pruners, a sharp knife, scissors), and leave about 1 inch of stem on the fruit. Refrigerate, unwashed, in the crisper drawer for up to one week.

Squash/Zucchini: Squash and zucchini are harvested when they reach about 6-8 inches in length. Have you ever thought you caught them all, and then, days later, discovered a torpedo-sized fruit among the foliage? While your monster squash might win you a contest somewhere, baseball bat fruits aren’t ideal for eating. The skin will be tough and the inside will be mostly wet, seedy membrane instead of creamy, melt-in-your-mouth squash. Be diligent about checking your plants at least every other day while they’re are producing. This regular harvesting will spur plant production and ensure your harvest doesn’t get ahead of you. To harvest, cut the fruit off the vine using a sharp blade (pruners, a sharp knife, scissors), and leave about 1 inch of stem on the fruit. Refrigerate, unwashed, in the crisper drawer for up to one week.

(illustration credit:

(illustration credit:  We thought we’d share how everything is doing in our Teaching Gardens now that we’re halfway through our season. Compare with your own gardens and let us know if you’re having similar luck (or misfortune) in your neck of the woods!

We thought we’d share how everything is doing in our Teaching Gardens now that we’re halfway through our season. Compare with your own gardens and let us know if you’re having similar luck (or misfortune) in your neck of the woods! BEETS– Eeks. Do we have to start with them? Leaf miner has been making a steady meal of the greens, despite our best efforts to squish the little white egg sacks on the leaf undersides. Our greens are also not especially green; they’ve gone reddish purple (and, no, they’re not a purple-leaf variety). Phosphorous deficiency? The wrong pH for beets, which prefer between 6.0 and 7.0? We’ll be soil testing in the fall to pin down the culprit.

BEETS– Eeks. Do we have to start with them? Leaf miner has been making a steady meal of the greens, despite our best efforts to squish the little white egg sacks on the leaf undersides. Our greens are also not especially green; they’ve gone reddish purple (and, no, they’re not a purple-leaf variety). Phosphorous deficiency? The wrong pH for beets, which prefer between 6.0 and 7.0? We’ll be soil testing in the fall to pin down the culprit.

SQUASH – It’s that time of the season. The zucchini and summer squash have begun producing and the recipes for using them up have begun to dot our Teaching Garden conversations.

SQUASH – It’s that time of the season. The zucchini and summer squash have begun producing and the recipes for using them up have begun to dot our Teaching Garden conversations. And that’s what’s growing in our Teaching Gardens! Let us know what you’re seeing in your own plots and we’ll keep you posted as the harvest continues. Happy gardening!

And that’s what’s growing in our Teaching Gardens! Let us know what you’re seeing in your own plots and we’ll keep you posted as the harvest continues. Happy gardening!

A scape is the flower stalk of the maturing garlic bulb. It begins as a straight stem, bends into a marked curlicue in early July, and then, as it prepares to open, straightens out again. In its early stages, the scape is most tender and ideal for harvest. Once the stem straightens out the second time, it becomes tougher, woody, and less desirable. The full harvest season lasts only a few weeks, so keep an eye on them or you’ll miss it!

A scape is the flower stalk of the maturing garlic bulb. It begins as a straight stem, bends into a marked curlicue in early July, and then, as it prepares to open, straightens out again. In its early stages, the scape is most tender and ideal for harvest. Once the stem straightens out the second time, it becomes tougher, woody, and less desirable. The full harvest season lasts only a few weeks, so keep an eye on them or you’ll miss it!

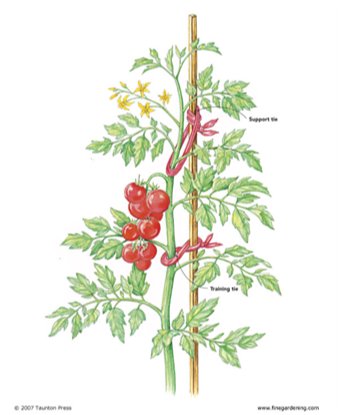

We use metal poles in our teaching gardens because wooden poles have the capacity to carry tomato blight (a devastating disease) from previous seasons. In contrast, metal poles may be reused for eons!

We use metal poles in our teaching gardens because wooden poles have the capacity to carry tomato blight (a devastating disease) from previous seasons. In contrast, metal poles may be reused for eons!

he tomato’s main stem, just above a side stem (in the “crotch”). A tomato plant will produce suckers throughout the growing season.

he tomato’s main stem, just above a side stem (in the “crotch”). A tomato plant will produce suckers throughout the growing season.